Dec 5 2017

Tumor-targeting nanoparticles filled with a drug that makes cancer cells more defenseless to chemotherapy’s toxicity could be used to treat a destructive and frequently deadly form of endometrial cancer, according to new study by the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy.

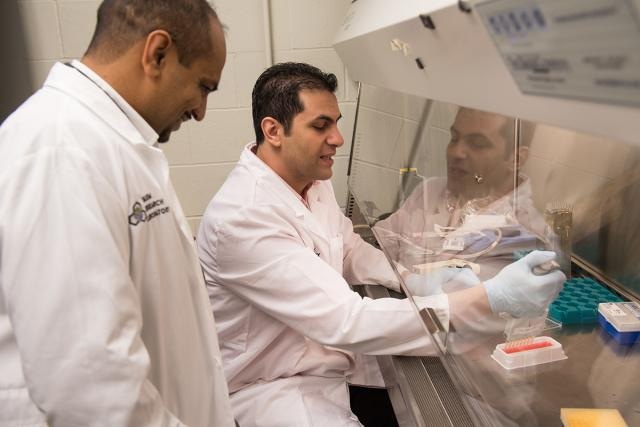

Aliasger K. Salem, professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the UI, and Kareem Ebeid, a UI pharmacy science graduate student, work in Salem’s laboratory. For the first time, researchers combined traditional chemotherapy with a relatively new cancer drug that attacks chemo-resistant tumor cells, loaded both into tiny nanoparticles, and created an extremely selective and lethal cancer treatment. Results of the three-year lab study were published in the journal “Nature Nanotechnology.” Photo by Tim Schoon.

Aliasger K. Salem, professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the UI, and Kareem Ebeid, a UI pharmacy science graduate student, work in Salem’s laboratory. For the first time, researchers combined traditional chemotherapy with a relatively new cancer drug that attacks chemo-resistant tumor cells, loaded both into tiny nanoparticles, and created an extremely selective and lethal cancer treatment. Results of the three-year lab study were published in the journal “Nature Nanotechnology.” Photo by Tim Schoon.

For the first time, researchers integrated traditional chemotherapy with a comparatively new cancer drug that attacks chemo-resistant tumor cells, loaded both into minute nanoparticles, and created a very selective and lethal cancer treatment. Results of the three-year lab research were published in the Nature Nanotechnology journal.

The new treatment could mean better survival rates for the approximately 6,000 U.S. women diagnosed with type II endometrial cancer annually and also signifies a vital step in the creation of targeted cancer therapies. Contrary to chemotherapy, the existing standard in cancer treatment that exposes the whole body to anti-cancer drugs, targeted treatments deliver drugs straight to the tumor site, thus protecting healthy tissue and organs and improving drug efficacy.

In this particular study, we took on one of the biggest challenges in cancer research, which is tumor targeting. And for the first time, we were able to combine two different tumor-targeting strategies and use them to defeat deadly type II endometrial cancer. We believe this treatment could be used to fight other cancers, as well.

Kareem Ebeid, Pharmacy Science Graduate Student, UI and Lead Researcher on the Study

In their effort to develop an extremely selective cancer treatment, Ebeid and his team began with minute nanoparticles. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using nanoparticles to treat cancer, mainly due to their small size. Tumors grow rapidly, and the blood vessels they make to feed their growth are flawed and full of holes. Nanoparticles are small enough to slip through the holes, thus allowing them to precisely target tumors.

The team then fueled the nanoparticles with two anti-cancer drugs: paclitaxel, a type of chemotherapy used to treat endometrial cancer, and nintedanib, or BIBF 1120, a comparatively new drug used to limit tumor blood vessel growth. However, in the UI study, the drug was used for a diverse purpose. In addition to limiting blood vessel growth, nintedanib also targets tumor cells with a particular mutation. The mutation, referred to as Loss of Function p53, disturbs the regular life cycle of tumor cells and makes them more resistant to the toxic effects of chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy destroys cells when they are in the process of mitosis, or cell division, and tumor cells with the Loss of Function p53 mutation frequently are stuck in a limbo state that decelerates this process. Cancers that are resistant to chemotherapy are a lot harder to treat and have less encouraging outcomes.

Nintedanib targets tumor cells with the Loss of Function p53 mutation and forces them to enter mitosis and divide, at which point they are more effortlessly killed by chemotherapy. Ebeid says this is the first time that researchers have used nintedanib to force tumor cells into mitosis and destroy them — a phenomenon researchers call “synthetic lethality.”

Basically, we are taking advantage of the tumor cells’ Achilles heel—the Loss of Function mutation—and then sweeping in and killing them with chemotherapy. We call this a synthetically lethal situation because we are creating the right conditions for massive cell death.

Kareem Ebeid

The treatment — and cellular death that it stimulates — could be applied to treat other cancers as well, including types of lung and ovarian cancers that also carry the Loss of Function p53 mutation.

We believe our research could have a positive impact beyond the treatment of endometrial cancer. We hope that since the drugs used in our study have already been approved for clinical use, we will be able to begin working with patients soon.

Aliasger K. Salem, Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, UI and Corresponding Author on the study

In the U.S. incidence and mortality rates for endometrial cancer have been on the rise in recent years, especially in the state of Iowa. Type I endometrial cancer, which feeds on the hormone estrogen, accounts for around 80% of new cases yearly. Type II endometrial cancer is less common, accounting for approximately 10% to 20% of cases, but is a lot more aggressive, resulting in 39% of total endometrial cancer deaths annually.

“For two decades, the standard therapy for type II endometrial cancer has been chemotherapy and radiation,” says Kimberly K. Leslie, professor and chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the UI Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine. “The possibility of a new treatment that is both highly selective and highly effective is incredibly exciting.”