Oct 5 2007

Microcrystals take the form of tiny grains resembling powder, which is extremely difficult to study. For the first time, researchers from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) and the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique used X-ray diffraction at the synchrotron to determine the structure of microcrystal grains of one cubic micrometre. They gained a factor of a thousand on the size of the analysable samples, opening up new research possibilities to chemists, physicists and biologists.

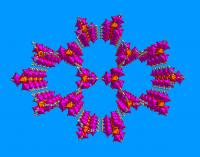

Crystalline structure of a microporous aluminium carboxylate determined at the ESRF by X-ray microdiffraction.

Crystalline structure of a microporous aluminium carboxylate determined at the ESRF by X-ray microdiffraction.

The properties of a crystal are determined by the arrangement of its atom in space, its crystalline structure. Scientists use X-ray or neutron diffraction to study crystalline structure when the size of the crystal is more than 10 cubic micrometres. Below this limit, the solid material is considered a powder. Scientists can apply powder diffraction to analyse such a material but this technique is not easy to exploit. Moreover, powder diffraction can only be used for materials with grain sizes of less than three millionths of a cubic micrometre. Due to these limitations, a determination of the structure of new synthetic solids in powder form is not always possible because the crystals are too small.

The teams from the ESRF and the Institute Lavoisier (CNRS/Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin) have used new set-up permitting X-ray diffraction on crystals of a size of one cubic micrometre, a volume a thousand times smaller than that ever attainable before. This new set-up consists of a focussing system for the ESRF beam, coupled with a goniometer, an instrument to position the sample with maximum precision.

The researchers studied the structure of an organic-inorganic hybrid compound (a microporous aluminium carboxylate), which could be used for gas absorption or to encapsulate various organic molecules. This study confirms that the new set-up allows pushing back the limits in crystal dimension accessible to X-ray diffraction.

“It is a revolution: what was considered a powder in the past has become a crystal today. Researchers can now bring forward samples left in their cupboards because the sizes had previously prevented their study. Now they will be able to elucidate the structures of these samples, with potentially great scientific advances on the horizon”, explains Thierry Loiseau, from the Institut Lavoisier.