Oct 24 2008

With a $1.6M grant from the U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR), UC San Diego NanoEngineering professor Joseph Wang will lead a project to create a "field hospital on a chip" that soldiers can wear on the battlefield.

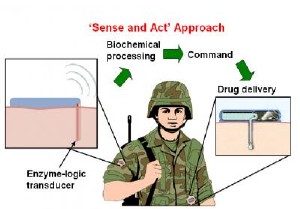

The automated sense-and-treat system being developed by UC San Diego NanoEngineering professor Joseph Wang and colleagues will continuously monitor a soldier’s sweat, tears or blood for biomarkers that signal common battlefield injuries such as trauma, shock, brain injury or fatigue. Once the system detects a battlefield injury, it will automatically administer the proper medication, thus beginning the treatment well before the soldier has reached a field hospital. Credit: UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

The automated sense-and-treat system being developed by UC San Diego NanoEngineering professor Joseph Wang and colleagues will continuously monitor a soldier’s sweat, tears or blood for biomarkers that signal common battlefield injuries such as trauma, shock, brain injury or fatigue. Once the system detects a battlefield injury, it will automatically administer the proper medication, thus beginning the treatment well before the soldier has reached a field hospital. Credit: UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

The automated sense-and-treat system will continuously monitor a soldier's sweat, tears or blood for biomarkers that signal common battlefield injuries such as trauma, shock, brain injury or fatigue. Once the system detects a battlefield injury, it will automatically administer the proper medication, thus beginning the treatment well before the soldier has reached a field hospital.

"Since the majority of battlefield deaths occur within the first 30 minutes after injury, rapid diagnosis and treatment are crucial for enhancing the survival rate of injured soldiers," said Joseph Wang, a NanoEngineering professor at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego and the Primary Investigator on the project.

To realize their "field hospital on a chip" idea, the engineers will need to build a minimally invasive system that monitors multiple biomarkers simultaneously and uses the system's "smarts" to process all this biomarker information and tease out accurate, automated diagnoses. These diagnoses would immediately trigger drug delivery or other medical intervention.

"Today's insulin and glucose management systems for patients with diabetes don't include smart sensors capable of performing complex logic operations," said Wang, who helped to develop the first noninvasive system for monitoring glucose from a patient's sweat. "We are working on a system that will be different. It will monitor biomarkers and make decisions about the type of injury a person has sustained and then begin treating that person accordingly," said Wang.

"Developing an effective interface between complex physiological processes and implantable devices could have a broader biomedical impact, providing autonomous, individual, 'on-demand' medical care, which is the goal of the new field of personalized medicine," said Wang.

To reach this level of automated diagnostic dexterity, the researchers plan to build upon "enzyme logic" breakthroughs recently demonstrated by Evgeny Katz, a Co-PI on the grant and the Milton Kerker Chaired professor of Chemistry and Biomolecular Science at Clarkson University.

Katz and colleagues demonstrated recently that enzymes can not only measure biomarkers, but also provide the logic necessary to make a limited set of diagnoses based on multiple biological variables.

One of the many challenges now facing Wang and his team, however, is to get the enzyme logic system to reliably work on sensing electrodes that humans can wear. Thus far, enzyme logic operations have only been demonstrated in solution.

From Biomarkers to 1s and 0s and Treatment

Lactate, oxygen, norepinephrine and glucose are examples as the kinds of injury biomarkers that will serve as biological input signals for their prototype logic system. Electrodes containing a combination of enzymes will serve as sensors and provide the logic necessary to convert the biomarkers to products which may then be picked up by another enzyme on the electrode for further logic operations. The electrodes will also act as transducers that produce strings of 1s and 0s that will activate smart materials that release medication based on predetermined treatment plans.

"We just want the ones and zeros. The pattern of ones and zeros will reveal the type of injury and automatically trigger the proper treatment," said Wang.

For example, if an injured soldier were to enter a state of shock, enzymes on the electrode would sense rising levels of the biomarkers lactate, glucose and norepinephrine. In turn, the concentrations of products generated by the enzymes would change—higher hydrogen peroxide, lower norepi-quinone, higher NADH and lower NAD+. This will cause the built-in logic structure to output the signal "1,0,1,0" which points to shock and will trigger a pre-determined treatment response.

"This is biocomputing in action," said Wang.

"We are just at the beginning of this project. During the first two years, our primary focus will be on the sensor systems. Integrating enzyme logic onto electrodes that can read biomarker inputs from the body will be one of our first major challenges," said Wang.

At the end of the four-year project, the researchers expect to have a working prototype that can detect different combinations of injury biomarkers thanks to the enzyme logic. At the same time, the researchers will also be working on signal-responsive membranes that can release drugs, as well as the electrical or optoelectronic systems that allow the sensors to communicate with the drug delivery system.

"We really hope that our enzyme-logic sense-and-treat system will revolutionize the monitoring and treatment of injured soldiers and lead to dramatic improvements in their survival rate," said Wang.