Feb 5 2009

Rice University materials scientists have put a new "twist" on carbon nanotube growth. The researchers found the highly touted nanomaterials grow like tiny molecular tapestries, woven from twisting, single-atom threads.

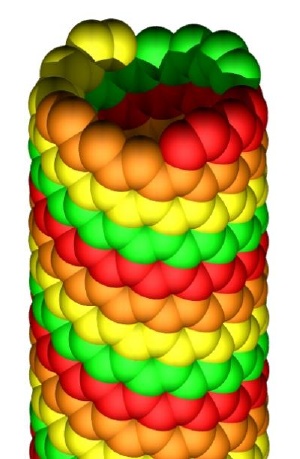

A new theory suggests nanotubes are 'woven' from twisting carbon threads. Credit: Morteza Bankehsaz/Rice University

A new theory suggests nanotubes are 'woven' from twisting carbon threads. Credit: Morteza Bankehsaz/Rice University

Carbon nanotubes are hollow tubes of pure carbon that measure about one nanometer, or one-billionth of a meter, in diameter. In molecular diagrams, they look like rolled-up sheets of chicken wire. And just like a roll of wire or gift-wrapping paper, nanotubes can be rolled at an odd angle with excess hanging off the end.

Though nanotubes are much-studied, their growth is poorly understood. They grow by "self assembly," forming spontaneously from gaseous carbon feedstock under precise catalytic circumstances. The new research, which appears online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, finds a direct relationship between a nanotube's "chiral" angle -- the amount it's twisted -- and how fast it grows.

"Our study offers some clues about this intimate 'self assembly' process," said Rice's Boris Yakobson, professor in mechanical engineering and materials science and of chemistry. New theory suggests that each tube is 'woven' from many twisting threads. Each grows independently, with new atoms attaching themselves to the exposed thread ends. The more threads there are, the faster the whole tapestry grows.

Yakobson, the lead researcher on the project, said the new formula's predictions have been borne out by a number of laboratory reports. For example, the formula predicts that nanotubes with the largest chiral angle will grow fastest because they have the most exposed threads -- something that's been shown in several experiments.

"Chirality is one of the primary determinants of a nanotube's properties," said Yakobson. "Our approach reveals quantitatively the role that chirality plays in growth, which is of great interest to all who hope to incorporate nanotubes into new technologies."

The study was co-authored by former Rice research scientist Feng Ding, now assistant professor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and Avetik Harutyunyan of the Honda Research Institute USA in Columbus, Ohio. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Welch Foundation and the Department of Defense.