Sep 29 2009

University of Michigan physicists have created the first atomic-scale maps of quantum dots, a major step toward the goal of producing "designer dots" that can be tailored for specific applications.

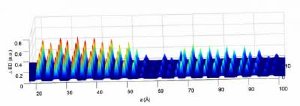

This is an atomic-scale map of the interface between an atomic dot and its substrate. Each peak represents a single atom. The map, made with high-intensity X-rays, is a slice through a vertical cross-section of the dot. Credit: Roy Clarke, University of Michigan

This is an atomic-scale map of the interface between an atomic dot and its substrate. Each peak represents a single atom. The map, made with high-intensity X-rays, is a slice through a vertical cross-section of the dot. Credit: Roy Clarke, University of Michigan

Quantum dots---often called artificial atoms or nanoparticles---are tiny semiconductor crystals with wide-ranging potential applications in computing, photovoltaic cells, light-emitting devices and other technologies. Each dot is a well-ordered cluster of atoms, 10 to 50 atoms in diameter.

Engineers are gaining the ability to manipulate the atoms in quantum dots to control their properties and behavior, through a process called directed assembly. But progress has been slowed, until now, by the lack of atomic-scale information about the structure and chemical makeup of quantum dots.

The new atomic-scale maps will help fill that knowledge gap, clearing the path to more rapid progress in the field of quantum-dot directed assembly, said Roy Clarke, U-M professor of physics and corresponding author of a paper on the topic published online Sept. 27 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Lead author of the paper is Divine Kumah of the U-M's Applied Physics Program, who conducted the research for his doctoral dissertation.

"I liken it to exploration in the olden days," Clarke said of dot mapping. "You find a new continent and initially all you see is the vague outline of something through the mist. Then you land on it and go into the interior and really map it out, square inch by square inch.

"Researchers have been able to chart the outline of these quantum dots for quite a while. But this is the first time that anybody has been able to map them at the atomic level, to go in and see where the atoms are positioned, as well as their chemical composition. It's a very significant breakthrough."

To create the maps, Clarke's team illuminated the dots with a brilliant X-ray photon beam at Argonne National Laboratory's Advanced Photon Source. The beam acts like an X-ray microscope to reveal details about the quantum dot's structure. Because X-rays have very short wavelengths, they can be used to create super-high-resolution maps.

"We're measuring the position and the chemical makeup of individual pieces of a quantum dot at a resolution of one-hundredth of a nanometer," Clarke said. "So it's incredibly high resolution."

A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter.

The availability of atomic-scale maps will quicken progress in the field of directed assembly. That, in turn, will lead to new technologies based on quantum dots. The dots have already been used to make highly efficient lasers and sensors, and they might help make quantum computers a reality, Clarke said.

"Atomic-scale mapping provides information that is essential if you're going to have controlled fabrication of quantum dots," Clarke said. "To make dots with a specific set of characteristics or a certain behavior, you have to know where everything is, so that you can place the atoms optimally. Knowing what you've got is the most important thing of all."