Mar 4 2010

Purdue University researchers have developed a miniature device capable of converting ultrafast laser pulses into bursts of radio-frequency signals, a step toward making wires obsolete for communications in the homes and offices of the future.

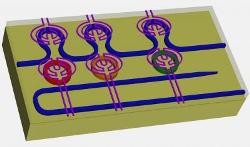

This diagram shows the design for new silicon "microring resonators," miniature devices used in a system that converts ultra fast laser pulses into bursts of radio-frequency signals.

This diagram shows the design for new silicon "microring resonators," miniature devices used in a system that converts ultra fast laser pulses into bursts of radio-frequency signals.

Such an advance could enable all communications, from high-definition television broadcasts to secure computer connections, to be transmitted from a single base station, said Minghao Qi, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering.

"Of course, ideas about specific uses of our technology are futuristic and speculative, but we envision a single base station and everything else would be wireless," he said. "This base station would be sort of a computer by itself, perhaps a card inserted into one of the expansion slots in a central computer. The central computer would take charge of all the information processing, a single point of contact that interacts with the external world in receiving and sending information."

Ordinarily, the continuous waves of conventional radio-frequency transmissions encounter interference from stray signals reflecting off of the walls and objects inside a house or office. However, the pulsing nature of the signals produced by the new "chip-based spectral shaper" reduces the interference that normally plagues radio frequency communications, said Andrew Weiner, Purdue's Scifres Family Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Each laser pulse lasts about 100 femtoseconds, or one-tenth of a trillionth of a second. These pulses are processed using "optical arbitrary waveform technology" pioneered by Purdue researchers led by Weiner.

Findings have appeared online in the journal Nature Photonics and were published in the February print issue of the magazine. The research is based at Purdue's Birck Nanotechnology Center in the university's Discovery Park.

"What enables this technology is that our devices generate ultrabroad bandwidth radio frequencies needed to transmit the high data rates required for high resolution displays," Weiner said.

Such a technology might eventually be developed to both receive and transmit signals.

"But initially, industry will commercialize devices that only receive signals, for 'one-way' traffic, such as television sets, projectors, monitors and printers," Qi said. "This is because the sending unit for transmitting data is currently still a little bulky. Later, if the sending unit can be integrated into the devices, we could enjoy full two-way traffic, enabling the wireless operation of things like hard-disc drives and computers."

The approach also might be used for transmitting wireless signals inside cars.

The researchers first create laser pulses with specific "shapes" that characterize the changing intensity of light from the beginning to end of each pulse. The pulses are then converted into radio frequency signals.

A key factor making the advance potentially useful is that the pulses transmit radio frequencies of up to 60 gigahertz, a frequency included in the window of the radio spectrum not reserved for military communications.

The Federal Communications Commission does not require a license to transmit signals from 57-64 gigahertz. This unlicensed band also is permitted globally, meaning systems using 60 gigahertz could be compatible worldwide.

"There is only a very limited window for civil operations, and 60 gigahertz falls within this window," Qi said.

Ordinary computer chips have difficulty transmitting electronic signals at such a rapid frequency because of "timing jitter," or the uneven timing with which transistors open and close to process information.

This uneven "clock" timing, or synchronization, of transistors does not hinder ordinary computer chips, which have a speed of about 3 gigahertz. However, for devices switching on and off at 60 gigahertz, this jitter prevents proper signal processing.

Another complication is that the digital-to-analog converters needed to convert pulsing laser light into radio frequency signals will not work at such high frequencies.

To sidestep these limitations, researchers have previously created "bulk optics" systems, which use mirrors, lenses and other optical components arranged on a vibration-dampened table several feet long to convert and transmit the pulsed signals.

However, these systems are far too large to be practical.

Now, the Purdue researchers have miniaturized the technology small enough to fit on a computer chip.

"We shrank the size of the bulk optical setup by thousands of times," Qi said.

The system is programmable so that it could be instructed to produce and transmit only certain frequencies, he said.

The researchers fabricated tiny silicon "microring resonators," devices that filter out certain frequencies and allow others to pass. A series of the microrings were combined in a programmable "spectral shaper" 100 microns wide, or about the width of a human hair. Each of the microrings is about 10 microns in diameter.

The microring filter can be tuned by heating the rings, which causes them to change so that they filter different frequencies. The research is funded by the National Science Foundation, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellowship program from the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Purdue filed a provisional patent in January for the technology, which is at least five years away from being ready for commercialization, Qi said.

Source: http://www.purdue.edu/