Mar 14 2010

For two decades, scientists have been pursuing a potential new way to treat bacterial infections, using naturally occurring proteins known as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Now, MIT scientists have recorded the first microscopic images showing the deadly effects of AMPs, most of which kill by poking holes in bacterial cell membranes.

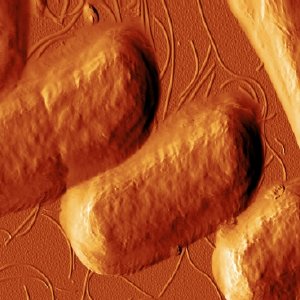

This image, taken with atomic force microscopy, shows E. coli bacteria after they have been exposed to the antimicrobial peptide CM15. The peptides have begun destroying the bacteria’s cell walls.

Image: Georg Fantner

This image, taken with atomic force microscopy, shows E. coli bacteria after they have been exposed to the antimicrobial peptide CM15. The peptides have begun destroying the bacteria’s cell walls.

Image: Georg Fantner

Researchers in the laboratory of MIT Professor Angela Belcher modified an existing, extremely sensitive technique known as high-speed atomic force microscopy (AFM) to allow them to image the bacteria in real time. Their method, described in this Sunday’s online edition of Nature Nanotechnology, represents the first way to study living cells using high-resolution images recorded in rapid succession.

Using this type of high-speed AFM could allow scientists to study how cells respond to other drugs and to viral infection, says Belcher, the Germeshausen Professor of Materials Science and Engineering and Biological Engineering and a member of the David H. Hoch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT. The new work could also help researchers understand how some bacteria can become resistant to AMPs (none of which have been approved as drugs yet).

Atomic force microscopy, invented in 1986, is widely used to image nanoscale materials. Its resolution is similar to that of electron microscopy, but unlike electron microscopy, it does not require a vacuum and thus can be used with living samples. However, traditional AFM requires several minutes to produce one image, so it cannot record a sequence of rapidly occurring events.

In recent years, scientists have developed high-speed AFM techniques, but haven’t optimized them for living cells. That’s what the MIT team set out to do, building on the experience of lead author Georg Fantner, a postdoctoral associate in Belcher’s lab who had worked on high-speed AFM at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

How they did it: Atomic force microscopy makes use of a cantilever equipped with a probe tip that “feels” the surface of a sample. Forces between the tip and the sample can be measured as the probe moves across the sample, revealing the shape of the surface. The MIT team used a cantilever about 1,000 times smaller than those normally used for AFM, which enabled them to increase the imaging speed without harming the bacteria.

With the new setup, the team was able to take images every 13 seconds over a period of several minutes. They found that AMP-induced cell death appears to be a two-step process: a short incubation period followed by a rapid “execution.” They were surprised to see that the onset of the incubation period varied from 13 to 80 seconds.

“Not all of the cells started dying at the exact same time, even though they were genetically identical and were exposed to the peptide at the same time,” says Roberto Barbero, a graduate student in biological engineering and an author of the paper.

Next steps: In the future, Belcher hopes to use atomic force microscopy to study other cellular phenomena, including the assembly of viruses in infected cells, and the effects of traditional antibiotics on bacterial cells. The technique may also prove useful in studying mammalian cells.

Funding: Erwin-Schrodinger Fellowship, National Institutes of Health, Army Research Office, Austrian Research Promotion Agency.

Source: “Kinetics of antimicrobial peptide activity measured on individual bacterial cells using high-speed atomic force microscopy,” Georg Fantner, Roberto Barbero, David Gray and Angela Belcher. Nature Nanotechology, March 14, 2010.