Mar 30 2010

Researchers at the University of South Florida have developed a technique to turn defects in graphene into tiny metallic wires

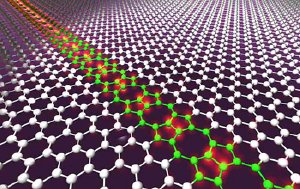

An artist's conception of a row of intentional molecular defects in a sheet of graphene. The defects effectively create a metal wire in the sheet. This discovery may lead to smaller yet faster computers in the future. Credit: Y. Lin, USF

An artist's conception of a row of intentional molecular defects in a sheet of graphene. The defects effectively create a metal wire in the sheet. This discovery may lead to smaller yet faster computers in the future. Credit: Y. Lin, USF

When most of us hear the word 'defect', we think of a problem that has to be solved. But a team of researchers at the University of South Florida (USF) created a new defect that just might be a solution to a growing challenge in the development of future electronic devices.

The team lead by USF Professors Matthias Batzill and Ivan Oleynik, whose discovery was published yesterday in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, have developed a new method for adding an extended defect to graphene, a one-atom-thick planar sheet of carbon atoms that many believe could replace silicon as the material for building virtually all electronics.

It is not simple to work with graphene, however. To be useful in electronic applications like integrated circuits, small defects must be introduced to the material. Previous attempts at making the necessary defects have either proved inconsistent or produced samples in which only the edges of thin strips of graphene or graphene nanoribbons possessed a useful defect structure. However, atomically-sharp edges are difficult to create due to natural roughness and the uncontrolled chemistry of dangling bonds at the edge of the samples.

The USF team has now found a way to create a well-defined, extended defect several atoms across, containing octagonal and pentagonal carbon rings embedded in a perfect graphene sheet. This defect acts as a quasi-one-dimensional metallic wire that easily conducts electric current. Such defects could be used as metallic interconnects or elements of device structures of all-carbon, atomic-scale electronics.

So how did the team do it? The experimental group, guided by theory, used the self-organizing properties of a single-crystal nickel substrate, and used a metallic surface as a scaffold to synthesize two graphene half-sheets translated relative to each other with atomic precision. When the two halves merged at the boundary, they naturally formed an extended line defect. Both scanning tunneling microscopy and electronic structure calculations were used to confirm that this novel one-dimensional carbon defect possessed a well-defined, periodic atomic structure, as well as metallic properties within the narrow strip along the defect.

This tiny wire could have a big impact on the future of computer chips and the myriad of devices that use them. In the late 20th century, computer engineers described a phenomenon called Moore's Law, which holds that the number of transistors that can be affordably built into a computer processor doubles roughly every two years. This law has proven correct, and society has been reaping the benefits as computers become faster, smaller, and cheaper. In recent years, however, some physicists and engineers have come to believe that without new breakthroughs in new materials, we may soon reach the end of Moore's Law. As silicon-based transistors are brought down to their smallest possible scale, finding ways to pack more on a single processor becomes increasingly difficult.

Metallic wires in graphene may help to sustain the rate of microprocessor technology predicted by Moore's Law well into the future. The discovery by the USF team, with support from the National Science Foundation, may open the door to creation of the next generation of electronic devices using novel materials. Will this new discovery be available immediately in new nano-devices? Perhaps not right away, but it may provide a crucial step in the development of smaller, yet more powerful, electronic devices in the not-too-distant future.

Source: National Science Foundation