Nov 2 2012

The human body has more than a trillion cells, most of them connected, cell to neighboring cells.

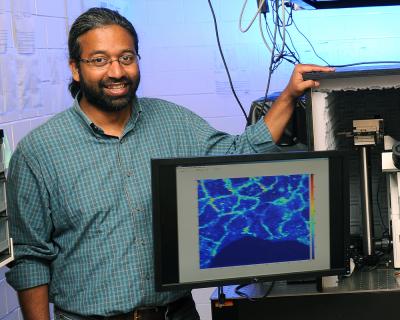

Sanjeevi Sivasankar leads a research team that uses atomic force microscopy and other technologies to study the bonds that connect biological cells. (Photo by Bob Elbert/Iowa State University)

Sanjeevi Sivasankar leads a research team that uses atomic force microscopy and other technologies to study the bonds that connect biological cells. (Photo by Bob Elbert/Iowa State University)

How, exactly, do those bonds work? What happens when a pulling force is applied to those bonds? How long before they break? Does a better understanding of all those bonds and their responses to force have implications for fighting disease?

Sanjeevi Sivasankar, an Iowa State assistant professor of physics and astronomy and an associate of the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory, is leading a research team that's answering those questions as it studies the biomechanics and biophysics of the proteins that bond cells together.

The researchers discovered three types of bonds when they subjected common adhesion proteins (called cadherins) to a pulling force: ideal, catch and slip bonds. The three bonds react differently to that force: ideal bonds aren't affected, catch bonds last longer and slip bonds don't last as long.

The findings have just been published by the online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sivasankar said ideal bonds – the ones that aren't affected by the pulling force – had not been seen in any previous experiments. The researchers discovered them as they observed catch bonds transitioning to slip bonds.

"Ideal bonds are like a nanoscale shock absorber," Sivasankar said. "They dampen all the force."

And the others?

"Catch bonds are like a nanoscale seatbelt," he said. "They become stronger when pulled. Slip bonds are more conventional; they weaken and break when tugged."

In addition to Sivasankar, the researchers publishing the discovery are Sabyasachi Rakshit, an Iowa State post-doctoral research associate in physics and astronomy and an Ames Laboratory associate; Kristine Manibog and Omer Shafraz, Iowa State doctoral students in physics and astronomy and Ames Laboratory student associates; and Yunxiang Zhang, a post-doctoral research associate for the University of California, Berkeley's California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences.

The project was supported by a $308,000 grant from the American Heart Association, a $150,000 Basil O'Connor Award from the March of Dimes Foundation and Sivasankar's Iowa State startup funds.

The researchers made their discovery by taking single-molecule force measurements with an atomic force microscope. They coated the microscope tip and surface with cadherins, lowered the tip to the surface so bonds could form, pulled the tip back, held it and measured how long the bonds lasted under a range of constant pulling force.

The researchers propose that cell binding "is a dynamic process; cadherins tailor their adhesion in response to changes in the mechanical properties of their surrounding environment," according to the paper.

When you cut your finger, for example, cells filling the wound might use catch bonds that resist the pulls and forces placed on the wound. As the forces go away with healing, the cells may transition to ideal bonds and then to slip bonds.

Sivasankar said problems with cell adhesion can lead to diseases, including cancers and cardiovascular problems.

And so Sivasankar said the research team is pursuing other studies of cell-to-cell bonds: "This is the beginning of a lot to be discovered about the role of these types of interactions in healthy physiology as well as diseases like cancer."