Mar 27 2013

Vision is that powerful ability to see situations clearly, not only for what they are, but also for what they can become. When you combine vision with supercomputing, you have a strong force for predicting the future.

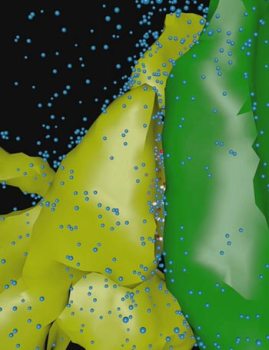

ICES researchers have begun automating construction of nano-scopic models of the human brain and its activity like this single chemical synapse between a (green) neuron segment and a (yellow) dendritic spine head surrounded by (blue) neurotransmitters.

ICES researchers have begun automating construction of nano-scopic models of the human brain and its activity like this single chemical synapse between a (green) neuron segment and a (yellow) dendritic spine head surrounded by (blue) neurotransmitters.

A decade ago researchers who conduct experiments in the virtual world of modeling and simulation began to collaborate in a new research institute and graduate program called the Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences (ICES). The institute’s work combines the use of computers, mathematics and various scientific disciplines to address formidable technological challenges including treatment of cardiovascular disease, new sources of energy, the design of advanced materials, nano-manufacturing and many more.

What starts as mathematical models and raw data is transformed through computer code and supercomputers into tangible trends, structures and patterns that need to be visualized. ICES uses the university’s visualization laboratory with “Stallion,” the world’s largest tiled display screen — which has 80 30-inch screens and more than 150 times the resolution of a standard high-definition screen — to examine results.

“Sometimes I tell students that computer modeling and simulation enables us to see the future,” says J. Tinsley Oden, the director of ICES. “We can explore the consequences of different decisions made well in advance of any actual decision. That will continue to be the strength of computational science.”

On March 26, the UT tower will shine orange to commemorate ICES’ 10th anniversary.

Models Reduce Guesswork

Since the beginning, ICES has worked closely with UT’s Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), which, in partnership with the National Science Foundation, operates some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world. ICES scientists make extensive use of the TACC supercomputers Lonestar and Stampede and their predecessors.

During the last decade the institute has significantly accelerated development of computational science. By using high-performance computers to simulate the real world in extreme detail, computational science removes dangerous guesswork.

For example, the Texas Division of Emergency Management used storm surge models developed by Clint Dawson, director of ICES’ Computational Hydraulics Group, to create evacuation plans during Hurricane Ike. ICES research has also impacted such diverse fields as cardiology, energy extraction and space flight.

To educate leaders in this relatively new science, ICES includes the prestigious Computational Science, Engineering and Mathematics (CSEM) graduate program. Graduate students work on a broad array of research topics. Atomic system modeling, gas well leakage, storm surge modeling and lung cancer drug development are interests mentioned by four students profiled earlier in the year by the institute.

With a highly selective philosophy, it currently enrolls 75 students. “It is intentionally kept small because we want to train future leaders in the discipline,” said Oden.

In total, ICES is home to 17 different research centers and groups that conduct research spanning the disciplines of biology, chemistry, engineering, physics, earth science, applied mathematics and more.

Some of the ICES research centers and groups were part of ICES’ predecessor, the Texas Institute for Applied Mathematics. Once forged, ICES soon added the $18.7 million U.S. Department of Energy Center for Predictive Engineering and Computational Sciences, and the $27 million KAUST-UT Austin Academic Excellence Alliance, a partnership with King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia that helped develop a cutting-edge university where only a sandlot existed five years ago, according to Oden.

Visionary Champions

The computational science at the core of this research enables ICES investigators to probe the world from the atomic up to the global scale, all under the same roof — named for visionary champions Peter and Edith O’Donnell Jr. Their name will be placed on the building that houses the institute to commemorate the unique organization’s 10th anniversary.

Consistent with their support of graduate-level engineering, science, and mathematics education, Peter and Edith O’Donnell Jr.’s foundation built what is now the O’Donnell Building (it was formerly called ACES) and gifted it to the university in 2000. The $32 million state-of-the-art 180,000-square-foot facility was built to house 300 graduate students and researchers, more than 70 faculty, and 60 annual visitors from industry and other universities. Located near the center of campus, the building was designed as an easily accessible home to the ICES interdisciplinary team, which draws faculty from 18 different departments from all over campus.

Facing — and modeling — the future in a newly renamed home, ICES will continue to be an important player in the advancement of science on and off the UT campus, said Oden, especially in the fields of medicine, energy and materials.

“I see a growth in the impact of computational science in virtually every aspect of human existence,” said Oden.