Nov 27 2013

Nanoparticles are used to produce sunscreens, scratch-resistant coatings, deodorants and other products, but researching their health effects began only recently.

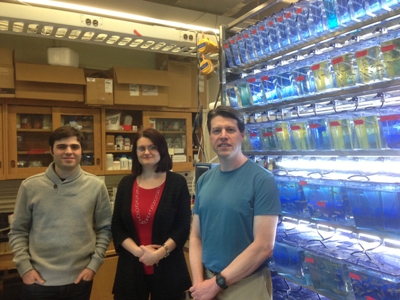

A Clarkson University research team has received a $305,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study how nanoparticles affect human health and the environment. Pictured are Rifat Emrah Ozel, a chemistry Ph.D. student at Clarkson, Silvana Andreescu, associate professor of chemistry & biomolecular science and Kenneth Wallace, associate professor of biology, next to tanks of zebrafish in a Clarkson biology lab. The team will be studying how nanoparticles affect the digestive tract of zebrafish embryos.

A Clarkson University research team has received a $305,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study how nanoparticles affect human health and the environment. Pictured are Rifat Emrah Ozel, a chemistry Ph.D. student at Clarkson, Silvana Andreescu, associate professor of chemistry & biomolecular science and Kenneth Wallace, associate professor of biology, next to tanks of zebrafish in a Clarkson biology lab. The team will be studying how nanoparticles affect the digestive tract of zebrafish embryos.

A Clarkson University team has received a three-year, $305,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study potential outcomes nanoparticles could have on human health and the environment. Clarkson Professors Silvana Andreescu and Kenneth Wallace are examining how nanoparticle exposure alters the antioxidant defense system present in cells, tissues and organs of exposed organisms.

The team will develop methodology to determine the concentration of free radicals within an organism resulting from nanoparticle exposure. Free radicals can damage cell membranes, proteins and DNA of affected cells resulting in inflammation and long-term health problems.

"There are currently no regulations for nanoparticle exposure. Differences in composition or quantity of nanoparticles can result in dramatic differences in toxicity. We are just beginning to understand how nanoparticles affect exposed tissues," said Andreescu, a professor of chemistry. "The results of this study will begin to provide an understanding of how nanoparticles interact with organ systems and ultimately affect our short- and long-term health."

The Clarkson team is using zebrafish to assess toxic reactions that would occur with human nanoparticle exposure. "Zebrafish are a great model system because they have a digestive tract that is similar in structure and function to the human system." said Wallace, an associate professor of biology.

Zebrafish embryos will be exposed to a variety of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles with varying levels of toxicity. Concentrations of free radicals within the digestive system will be determined with microelectrochemical probes developed during this study.

"Surfaces within the digestive system can have long-term exposure when nanoparticles are ingested. The inside of the digestive system where food passes is highly folded and can retain nanoparticles. As a result, toxic effects of nanoparticles will likely be more concentrated in this system," said Wallace.

The project will create a new framework for assessing nanotoxicity and provide a clearer picture of the relationship between nanoparticle exposure and human health, Wallace and Andreescu said. It may also help develop guidelines to modify nanoparticles and their use in the future.

The research will also give rise to a class on environmental health and safety implications of nanotechnology for students in Clarkson’s chemistry, biotechnology, materials science and environmental science and engineering programs. The curriculum will be broadly disseminated to nearby four-year colleges and the Clarkson website.