A team led by the Lawrence Livermore scientists has created a new kind of ion channel based on short carbon nanotubes, which can be inserted into synthetic bilayers and live cell membranes to form tiny pores that transport water, protons, small ions and DNA.

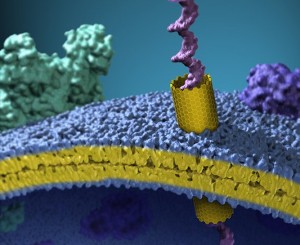

An artist’s view of a carbon nanotube inserted in a plasma membrane of a cell. The nanotube forms a nanoscale tunnel in the membrane and the image shows a single long strand of DNA passing through that tunnel.

An artist’s view of a carbon nanotube inserted in a plasma membrane of a cell. The nanotube forms a nanoscale tunnel in the membrane and the image shows a single long strand of DNA passing through that tunnel.

These carbon nanotube "porins" have significant implications for future health care and bioengineering applications. Nanotube porins eventually could be used to deliver drugs to the body, serve as a foundation of novel biosensors and DNA sequencing applications, and be used as components of synthetic cells.

Researchers have long been interested in developing synthetic analogs of biological membrane channels that could replicate high efficiency and extreme selectivity for transporting ions and molecules that are typically found in natural systems. However, these efforts always involved problems working with synthetics and they never matched the capabilities of biological proteins.

Unlike taking a pill which is absorbed slowly and is delivered to the entire body, carbon nanotubes can pinpoint an exact area to treat without harming the other organs around.

"Many good and efficient drugs that treat diseases of one organ are quite toxic to another," said Aleksandr Noy, an LLNL biophysicist who led the study and is the senior author on the paper appearing in the Oct. 30 issue of the journal, Nature. "This is why delivery to a particular part of the body and only releasing it there is much better."

The Lawrence Livermore team, together with colleagues at the Molecular Foundry at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of California Merced and Berkeley campuses, and University of Basque Country in Spain created a new type of a much more efficient, biocompatible membrane pore channel out of a carbon nanotube (CNT) -- a straw-like molecule that consists of a rolled up graphene sheet.

This research showed that despite their structural simplicity, CNT porins display many characteristic behaviors of natural ion channels: they spontaneously insert into the membranes, switch between metastable conductance states, and display characteristic macromolecule-induced blockades. The team also found that, just like in the biological channels, local channel and membrane charges could control the ionic conductance and ion selectivity of the CNT porins.

"We found that these nanopores are a promising biomimetic platform for developing cell interfaces, studying transport in biological channels, and creating biosensors," Noy said. "We are thinking about CNT porins as a first truly versatile synthetic nanopore that can create a range of applications in biology and materials science."

"Taken together, our findings establish CNT porins as a promising prototype of a synthetic membrane channel with inherent robustness toward biological and chemical challenges and exceptional biocompatibility that should prove valuable for bionanofluidic and cellular interface applications," said Jia Geng, a postdoc who is the first co-author of the paper.

Kyunghoon Kim, a postdoc and another co-author, added: "We also expect that our CNT porins could be modified with synthetic 'gates' to dramatically alter their selectivity, opening up exciting possibilities for their use in synthetic cells, drug delivery and biosensing."