Jul 24 2019

A new generation of pathology labs placed on chips is set to transform the detection and treatment of cancer by employing devices as thin as a human hair to examine bodily fluids.

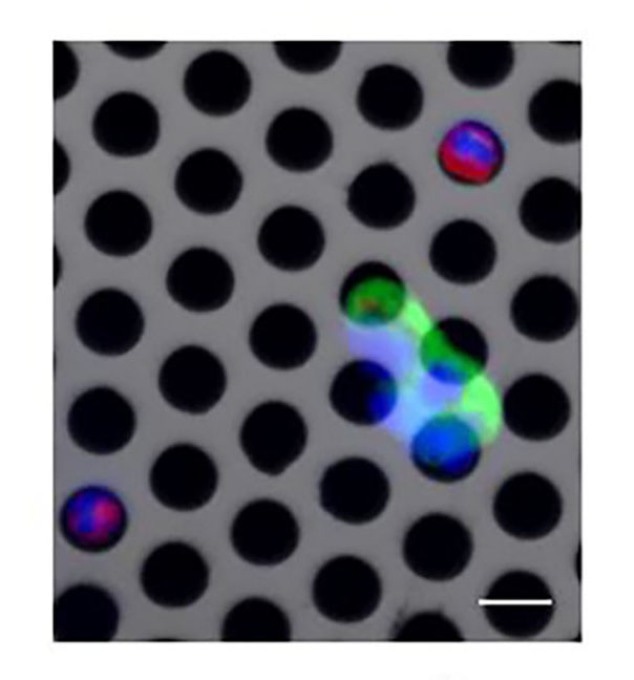

Circulating tumor cells trapping on a porous membrane using microfluidics (the scale bar is 10 µm). (Image credit: Florina Silvia Iliescu)

Circulating tumor cells trapping on a porous membrane using microfluidics (the scale bar is 10 µm). (Image credit: Florina Silvia Iliescu)

The technology, called microfluidics, promises portable, economical devices that could not only enable extensive screening for early signs of cancer but also help to create personalized treatments for patients, said Ciprian Iliescu, a co-author of a review of microfluidic techniques for cancer analysis published in the journal Biomicrofluidics, from AIP Publishing.

If you isolate some cells and expose them to drug candidates, you can predict the response of the patient in advance. Then you can track how the tumor is evolving in response to treatment.

Ciprian Iliescu, Review Co-Author and Researcher, IMT-Bucharest

The devices scan saliva, blood, or urine for specific cells, proteins or tissue that are formed by tumors and then spread all over the body.

The use of fluids as a liquid biopsy, rather than a conventional solid biopsy from a tumor, has numerous benefits. It is less invasive, minimizing patient discomfort, and also offers information about hard-to-access tumors, such as in fetus.

Since the biological clues, or biomarkers, of cancer wind up in the bloodstream, a liquid biopsy can give a clear picture of genomic state of all cancer in the body, including at its main site and if it has spread. The researchers refer to these insights as understanding the “global molecular status of the patient.”

The biggest difficulty is the diversity of cancer. Each of the over 100 identified cancers have their own biomarkers, which the authors categorize into four groups: cellular aggregates (circulating tumor microemboli); platelets and cellular vesicles (exosomes); free cells (circulating endothelial progenitor cells, circulating tumor cells, and cancer stem cells); and macro- and nanomolecules (proteins and nucleic acids).

A wide variety of microfluidic devices are being engineered to isolate these biomarkers, making the best use of the advancement in nanofabrication over the last few decades. Multifaceted structures, such as forked flow channels, spirals, pillars, and pools, precisely sieve and regulate flow rates, while surfaces contain molecules that attract specific species. Certain devices also use magnetic, electrical, or acoustic fields to help choose the biomarker target and even have smart, integrated electronic circuits for data processing.

Already some devices have entered the market, such as CellSearch, which isolate circulating tumor cells. However, faster and more sensitive systems are being built for many types of cancer biomarkers.

Integrating more than one technique may help with precision; however, this will be at the cost of speed. Sensitivity can also be enhanced by culturing the biomarkers to boost their concentration. Iliescu said the field holds promise but is still in its early stages.

“We need more and more clinical tests to bring this technology to maturity,” he said.