Jul 24 2007

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has developed an improved version of a real-time magnetic microscopy system that converts evidence of tampering on magnetic audio and video tapes—erasing, overdubbing and other alterations—into images with four times the resolution previously available. This system is much faster than conventional manual analysis and offers the additional benefit of reduced risk of contaminating the tapes with magnetic powder. NIST recently delivered these new capabilities to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for validation as a forensic tool.

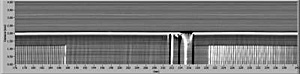

This image, produced by the new NIST forensic tape analysis system, clearly reveals an overdubbing. The new recording is visible from the left bottom of the image to about 188 millimeters on the distance counter, the large smudge at 216 mm was made by the erase head, and the original recording is visible starting at about 220 mm.

This image, produced by the new NIST forensic tape analysis system, clearly reveals an overdubbing. The new recording is visible from the left bottom of the image to about 188 millimeters on the distance counter, the large smudge at 216 mm was made by the erase head, and the original recording is visible starting at about 220 mm.

Earlier versions of this system made images with a resolution of about 400 dots per inch (dpi). The new system uses four times as many magnetic sensors, 256, embedded on a NIST-made silicon chip that serves as a read head in a modified cassette tape deck. The NIST read head operates adjacent to a standard read head, enabling investigators to listen to a tape while simultaneously viewing the magnetic patterns on a computer monitor. Each sensor in the customized read head changes electrical resistance in response to magnetic field patterns detected on the tape. NIST developed the mechanical system for extracting a tape from its housing and transporting it over the read heads, the electronics interface, and software that convert maps of sensor resistance measures into digital images.

The upgrade included quadrupling the image resolution to 1600 dpi, the capability to scan both video and audio tapes, complete computer control of tape handling, and the capability to digitize the audio directly from the acquired image. The software displays the audio magnetic track pattern from the tape to identify tiny features, from over-recording marks to high-intensity signals from gunshots. The system is designed to analyze analog tapes but could be converted to work with digital tapes, according to project leader David Pappas.

The new nanoscale magnetic microscope also has been used experimentally for non-destructive evaluation of integrated circuits. By mapping tiny changes in magnetic fields across an integrated circuit, the device can build up an image of current flow and densities much faster and in greater detail than the single-sensor scanners currently used by the chip industry, says Pappas.