Feb 27 2008

A novel technique for vaccinating against a variety of infectious diseases – using an oil-based emulsion placed in the nose, rather than needles – has proved able to produce a strong immune response against smallpox and HIV in two new studies.

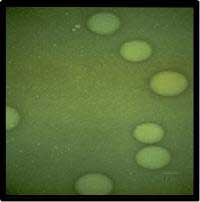

High energy oil-in-water emulsions used in the U-M vaccines are made up of droplets 200 nanometers in size.

High energy oil-in-water emulsions used in the U-M vaccines are made up of droplets 200 nanometers in size.

The results build on previous success in animal studies with a nasal nanoemulsion vaccine for influenza, reported by University of Michigan researchers in 2003.

Nanoemulsion vaccines developed at the Michigan Nanotechnology Institute for Medicine and the Biological Sciences at U-M are based on a mixture of soybean oil, alcohol, water and detergents emulsified into ultra-small particles smaller than 400 nanometers wide, or 1/200th the width of a human hair. These are combined with part or all of the disease-causing microbe to trigger the body’s immune response.

A team led by U-M scientist James Baker Jr., M.D., the institute’s director, pioneered the technology, for which a patent was recently awarded to U-M.

“The two studies show the nanoemulsion platform is capable of developing vaccines from very diverse materials. We used whole virus in the smallpox vaccine. In the HIV vaccine, we used a single protein. We were able to promote an immune response using either source,” says Baker.

The technology is licensed to NanoBio Corp., an Ann Arbor-based biotech company which Baker founded in 2000 and in which he has a financial interest. Baker is the Ruth Dow Doan Professor of internal medicine and Allergy Division chief at the U-M Medical School.

The surface tension of the nanoparticles disrupts membranes and destroys microbes but does not harm most human cells due to their location within body tissues. Nanoemulsion vaccines are highly effective at penetrating the mucous membranes in the nose and initiating strong and protective types of immune response, Baker says. U-M researchers are also exploring nasal nanoemulsion vaccines to protect against bioterrorism agents and hepatitis B.

The smallpox results, which appear in the February issue of Clinical Vaccine Immunology, could lead to an effective human vaccine against smallpox that is safer than the present live-vaccinia virus vaccine because it would use nanoemulsion-killed vaccinia virus, says Baker.

Anna U. Bielinska, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in internal medicine at the U-M Medical School, and others on Baker’s research team developed a killed-vaccinia virus nanoemulsion vaccine which they placed in the noses of mice to trigger an immune response. They found the vaccine produced both mucosal and antibody immunity, as well as Th1 cellular immunity, an important measure of protective immunity.

When the mice were exposed to live vaccinia virus to test the vaccine’s protective effect, all of them survived, while none of the unvaccinated control mice did. The researchers conclude that the nanoemulsion vaccinia vaccine offers protection equal to that of the existing vaccine, without the risk of using a live virus or the need for an inflammatory adjuvant such as alum hydroxide.

“We found that the nanoemulsion vaccine could inactivate and kill the virus and then subsequently induce immunity to the virus that includes cellular immunity, antibody immunity and mucosal immunity,” Baker says.

In antibody immunity, antibodies bind invading microbes as they circulate through the body. In cellular immunity, the immune system attacks invaders inside infected cells. There is growing interest in vaccines that induce mucosal immunity, in which the immune system stops and kills the invader in mucous membranes before it enters body systems.

A National Institutes of Health program, the Great Lakes Regional Centers of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, funded the research. If the federal government conducts further studies and finds the nanoemulsion smallpox vaccine effective in people, it could be a safer way to protect citizens and health care workers in the event of a bioterrorism attack involving smallpox, Baker says.

That would allay concerns about the current vaccine’s safety which arose in 2002. On the eve of the Iraq War, the Bush administration proposed a voluntary program to vaccinate military personnel and 500,000 health care workers with the existing vaccine to prepare for the possible use of smallpox virus as a biological weapon.

Relatively few health care workers volunteered to get the vaccine, amid concerns that the live vaccinia virus used in the vaccine can be transmitted to other people for a time and can pose a serious risk to people with weakened immune systems and certain skin conditions. As of mid-2007, more than 1.2 million military personnel received smallpox shots. Small percentages of those vaccinated subsequently have had heart and neurological adverse effects.

Baker’s team has published results from a preliminary test of a nanoemulsion vaccine’s effectiveness against HIV in the February issue of AIDS Research Human Retroviruses.

It is becoming widely acknowledged that standard approaches to vaccines against HIV have not worked. Baker says the HIV nanoemulsion vaccine tested in the noses of mice in the study represents “a different approach in the way it produces immunity and the type of immunity produced.”

Vaccines administered in the nose are also able to induce mucosal immunity in the genital mucosa. Evidence is growing that HIV virus can infect the mucosal immune system.

“Therefore, developing mucosal immunity may be very important for protection against HIV,” Baker says, adding that previous vaccine approaches have not aimed to do that.

In the study, the nanoemulsion HIV vaccine showed it was able to induce mucosal immunity, cellular immunity and neutralizing antibody to various isolates of HIV virus. A protein used by the team, gp120, is one of the major binding proteins under study in other HIV vaccine approaches.

“This was an exploratory study to see if further research is warranted,” Baker says. His team plans further research to test the concept in animal models, potentially with whole viral vaccines or ones with multiple protein components.