Jan 29 2009

In the race to develop the next generation of storage and recording media, a major hurdle has been the difficulty of studying the tiny magnetic structures that will serve as their building blocks. Now a team of physicists at the University of California, Davis, has developed a technique to capture the magnetic "fingerprints" of certain nanostructures - even when they are buried within the boards and junctions of an electronic device. This breakthrough in nanomagnetism was published in the Jan. 19 issue of Applied Physics Letters.

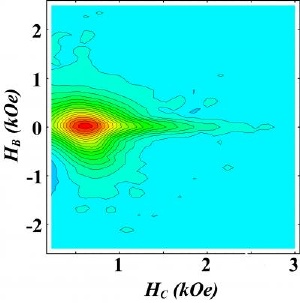

This magnetic fingerprint, or "FORC distribution," of 10-nanometer-thick cobalt nanodisks shows that all the magnetic moments are pointing in the same direction. Credit: Kai Liu/UC Davis

This magnetic fingerprint, or "FORC distribution," of 10-nanometer-thick cobalt nanodisks shows that all the magnetic moments are pointing in the same direction. Credit: Kai Liu/UC Davis

The past decade has witnessed a thousand-fold increase in magnetic recording area density, which has revolutionized the way information is stored and retrieved. These advances are based on the development of nanomagnet arrays which take advantage of the new field of spintronics: using electron spin as well as charge for information storage, transmission and manipulation.

But due to the miniscule physical dimensions of nanomagnets – some are as small as 50 atoms wide – observing their magnetic configurations has been a challenge, especially when they are not exposed but built into a functioning device.

"You can't take full advantage of these nanomagnets unless you can 'see' and understand their magnetic structures – not just how the atoms and molecules are put together, but how their electronic and magnetic properties vary accordingly," said Kai Liu, a professor and Chancellor's Fellow in physics at UC Davis. "This is difficult when the tiny nanomagnets are embedded and when there are billions of them in a device."

To tackle this challenge, Liu and three of his students, Jared Wong, Peter Greene and Randy Dumas, created copper nanowires embedded with magnetic cobalt nanodisks. Then they applied a series of magnetic fields to the wires and measured the responses from the nanodisks. By starting each cycle at full saturation – that is, using a field strong enough to align all the nanomagnets – then applying a progressively more negative field with each reversal, they created a series of information-rich graphic patterns known to physicists as "first-order reversal curve (FORC) distributions."

"Each pattern tells us a different story about what's going on inside the nanomagnets," Liu said. "We can see how they switch from one alignment to another, and get quantitative information about how many nanomagents are in one particular phase: for example, whether the magnetic moments are all pointing in the same direction or curling around a disk to form vortices. This in turn tells us how to encode information with these nanomagnets."

The technique will be applicable to a wide variety of physical systems that exhibit the kind of lag in response time (or hysteresis) as magnets, including ferroelectric, elastic and superconducting materials, Liu explained. "It's a powerful tool for probing variations, or heterogeneity, in the system, and real materials always have a certain amount of this."

Other collaborators include Daniel Masiel, a graduate student in chemistry; Nigel Browning, professor of chemical engineering and materials science; Kenneth Verosub, professor of geology, and physics professors Richard Scalettar and Gergely Zimanyi.

The study was supported in part by grants from the Center for Information Technology and Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS), the National Science Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.