Sep 3 2009

PTB researchers want to construct the "atomic clock of the future" much more simply and more compactly than the previous elaborate laboratory set-ups.

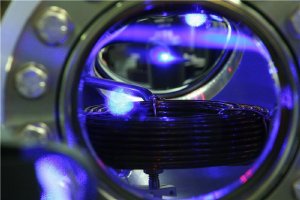

View into the ultrahigh vacuum chamber in which strontium atoms are cooled and stored. In the upper third of the window, the blue fluorescent light of a cloud of cold strontium atoms (Sr) is to be seen. (Image: PTB)

View into the ultrahigh vacuum chamber in which strontium atoms are cooled and stored. In the upper third of the window, the blue fluorescent light of a cloud of cold strontium atoms (Sr) is to be seen. (Image: PTB)

You imagine a clock to be different – yet the optical table with its many complicated set-ups really is one. Optical clocks like the strontium clock in the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) in Braunschweig could be the atomic clocks of the future; some of them though are already ten times more precise and stable than the best primary caesium atomic clocks. Now they might also become more compact and even portable, maybe in the future even travel to space. PTB scientists have shown how some fundamental difficulties, which a more simple set-up had previously hindered, could be avoided. They have written about this in the current edition of the journal "Physical Review Letters". In the next step they want to build such a clock. They already have a practical application in mind: the clock could help to determine geographical heights even more exactly than before.

An optical clock is so exact because its "pendulum" swings so quickly. The same effect that makes a quartz clock more precise than a classical grandfather clock is behind this: the periodically swinging element within, the oscillating quartz crystal, moves by far more quickly than the pendulum of the grandfather clock; thus the scale can to some extent be divided more precisely and also be more precisely checked. The "pendulum" of a caesium atomic clock swings even more quickly: i.e. that microwave radiation which can bring about a spin change in each electron of a caesium atom. Precisely the microwave frequency at which this effect is largest defines the second. An optical atomic clock works with the still higher frequency of optical radiation - that is with an even faster pendulum.

As the movement of the atoms leads to very large frequency shifts through the Doppler effect, in the best of these clocks the atoms are slowed down to a hundredth of the speed of a pedestrian in a first preparation step with the aid of laser cooling. In a lattice clock a further step then follows in which the atoms are held in potential wells. These are created through the intensive light field of a laser. Several tens of thousands of strontium atoms are trapped in this so-called optical lattice. The movement of the atoms is thus limited to the fraction of an optical wavelength, so that shifts through the Doppler effect can be ignored.

A few hundred atoms which can disturb each other are trapped in each potential well. If the isotope strontium-87, a fermion, is used, two of these particles do not come close to each other at very low temperatures due to the Pauli principle. That is the reason why this isotope is used to construct optical clocks. But as it can only be cooled relatively complicatedly with laser light and, moreover, only has a natural abundance of 7 %, it is, in principle, not so well suited for simple, transportable clocks or even for clocks suitable for space.

The isotope strontium-88 with over 80 % natural abundance, which is also easier to cool, is, however, a boson. That means that even at the lowest temperatures many collisions between the atoms occur. They can lead to losses and to a shift and broadening of the reference line. How strongly these collisions influence the accuracy of the clock was, however, not known previously. In an experiment at PTB, these influences have now been measured in detail for the first time. The results of the investigation have shown how the optical lattice has to be dimensioned and how many atoms may be stored in it to operate a very accurate lattice clock also with strontium-88. A clock is now being built on this basis which is more compact and more transportable than the previous lattice clocks.

The gravitational red shift of the earth, amounting to a height difference of 10–16 per meter on its surface, is being discussed as a possible first use for the precise determination of the height over the geoid. So the clock could be used to improve, for example, gravitation maps.