Dec 13 2010

The discoveries of superconductivity, the quantum Hall effect and the fractional quantum Hall effect were all the result of measurements made at increasingly lower temperatures.

Now, pushing the regime of the very cold into the very small, a research team from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the University of Maryland, Janis Research Company, Inc., and Seoul National University, has designed and built the most advanced ultra-low temperature scanning probe microscope (ULTSPM) in the world.

Detailed in a recent paper, the ULTSPM operates at lower temperatures and higher magnetic fields than any other similar microscope, capabilities that enable the device to resolve energy levels separated by as small as 1 millionth of an electron volt. This extraordinary resolution has already resulted in the discovery of new physics (see "Puzzling New Physics from Graphene Quartet's Quantum Harmonies").

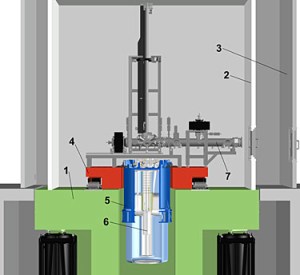

The ULTSPM lab rests on a separate 110-ton concrete slab (1), supported by pneumatic isolators. Inner (2) and an outer (3) enclosures shield from acoustic noise, with the inner enclosure also acting as a radio-frequency shield. The microscope is mounted on a 6-ton granite table (4), also supported by pneumatic isolators. The cryostat (5) is mounted in a hole in the granite table and in the concrete slab on a third set of pneumatic isolators. Inside the cryostat, the dilution refrigerator insert (6) hangs immersed in the liquid helium bath. Samples from the processing lab enter the enclosed room through two hatches on the right via a central vacuum line (7).

The ULTSPM lab rests on a separate 110-ton concrete slab (1), supported by pneumatic isolators. Inner (2) and an outer (3) enclosures shield from acoustic noise, with the inner enclosure also acting as a radio-frequency shield. The microscope is mounted on a 6-ton granite table (4), also supported by pneumatic isolators. The cryostat (5) is mounted in a hole in the granite table and in the concrete slab on a third set of pneumatic isolators. Inside the cryostat, the dilution refrigerator insert (6) hangs immersed in the liquid helium bath. Samples from the processing lab enter the enclosed room through two hatches on the right via a central vacuum line (7).

"To get these kinds of measurements, you need to combine coarse and extremely fine movement (the mechanical positioning of a probe tip about two atoms' distance from the sample surface), ultra-high vacuum, cryogenics and vibration isolation," says NIST Fellow Joseph Stroscio, one of the device's co-creators. "We designed this instrument to achieve superlative levels of performance, which, in turn, requires achieving nearly the ultimate in environmental control."

The NIST team had to overcome many technical challenges to achieve this level of precision and sensitivity, according to Young Jae Song, a postdoctoral researcher who helped develop the instrument at NIST.

Past designs used mechanical systems to move the probe tip that did not work over a wide range of temperatures. Researchers overcame this by creating piezoelectric actuators that expand with atomic scale precision when voltage is applied.

For vibration control, the group built the ULTSPM facility on top of a separate 110-ton concrete block buffered by six computer-controlled air springs. The ULTSPM, itself, sits on a 6-ton granite table, isolated from the concrete block by another set of computer-controlled air springs.

To achieve the ULTSPM's ultra low operating temperature of 10 millikelvins, the team designed a low noise dilution refrigerator to supplement the device's chilly 3-meter deep, 250-liter liquid helium bath. Because electromagnetic radiation entering through wires and cables can heat up the microscope, the ULTSPM lab is nested inside a separate, electromagnetically shielded room.

In order to ready new samples and probes without disturbing ongoing measurements, experimenters built a vacuum-sealed "railroad" system that they can disconnect from the chamber.

"The ability to create these kinds of experimental conditions opens up a whole new frontier in nanoscale physics," says Robert Celotta, founding director of the NIST Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology. "This instrument has been five years in the making, and we can't help but be excited about all the discoveries waiting to be made."

Source: http://nist.gov/cnst/