Mar 2 2013

A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

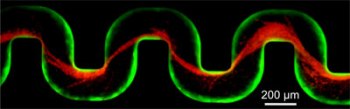

Over a period of about 40 hours, bac¬te¬r¬ial cells (green) flowed through a chan¬nel, form-ing a green biofilm on the walls. Over the next ten hours, researchers sent red bac¬te¬r¬ial cells through the chan¬nel. The red cells became stuck in the sticky biofilm and began to form thin red stream¬ers. Once stuck, these stream¬ers in turn trapped addi¬tional cells, lead¬ing to rapid clog¬ging. Credit: Knut Drescher, Princeton University

Over a period of about 40 hours, bac¬te¬r¬ial cells (green) flowed through a chan¬nel, form-ing a green biofilm on the walls. Over the next ten hours, researchers sent red bac¬te¬r¬ial cells through the chan¬nel. The red cells became stuck in the sticky biofilm and began to form thin red stream¬ers. Once stuck, these stream¬ers in turn trapped addi¬tional cells, lead¬ing to rapid clog¬ging. Credit: Knut Drescher, Princeton University

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Click on the image to view movie. Over a period of about 40 hours, bacterial cells (green) flowed through a channel, forming a green biofilm on the walls. Over the next ten hours, researchers sent red bacterial cells through the channel. The red cells became stuck in the sticky biofilm and began to form thin red streamers. Once stuck, these streamers in turn trapped additional cells, leading to rapid clogging. (Image source: Knut Drescher)

Using time-lapse imaging, researchers at Princeton University monitored fluid flow in narrow tubes or pores similar to those used in water filters and medical devices. Unlike previous studies, the Princeton experiment more closely mimicked the natural features of the devices, using rough rather than smooth surfaces and pressure-driven fluid instead of non-moving fluid.

The team of biologists and engineers introduced a small number of bacteria known to be common contaminants of medical devices. Over a period of about 40 hours, the researchers observed that some of the microbes — dyed green for visibility — attached to the inner wall of the tube and began to multiply, eventually forming a slimy coating called a biofilm. These films consist of thousands of individual cells held together by a sort of biological glue.

Over the next several hours, the researchers sent additional microbes, dyed red, into the tube. These red cells became stuck to the biofilm-coated walls, where the force of the flowing liquid shaped the trapped cells into streamers that rippled in the liquid like flags rippling in a breeze. During this time, the fluid flow slowed only slightly.

At about 55 hours into the experiment, the biofilm streamers tangled with each other, forming a net-like barrier that trapped additional bacterial cells, creating a larger barrier which in turn ensnared more cells. Within an hour, the entire tube became blocked and the fluid flow stopped.

The study was conducted by lead author Knut Drescher with assistance from technician Yi Shen. Drescher is a postdoctoral research associate working with Bonnie Bassler, Princeton's Squibb Professor in Molecular Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and Howard Stone, Princeton's Donald R. Dixon '69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

"For me the surprise was how quickly the biofilm streamers caused complete clogging," said Stone. "There was no warning that something bad was about to happen."

By constructing their own controlled environment, the researchers demonstrated that rough surfaces and pressure driven flow are characteristics of nature and need to be taken into account experimentally. The researchers used stents, soil-based filters and water filters to prove that the biofilm streams indeed form in real scenarios and likely explain why devices fail.

The work also allowed the researchers to explore which bacterial genes contribute to biofilm streamer formation. Previous studies, conducted under non-realistic conditions, identified several genes involved in formation of the biofilm streamers. The Princeton researchers found that some of those previously identified genes were not needed for biofilm streamer formation in the more realistic habitat.