Sep 6 2013

By blending their expertise, two materials science engineers at Washington University in St. Louis changed the electronic properties of new class of materials — just by exposing it to light.

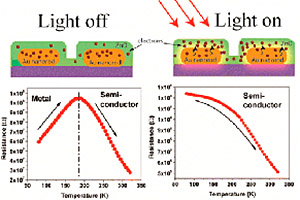

This image shows how electrons in the gold nanorods get excited when exposed to light, then are absorbed into a thin film of zinc oxide, changing the properties of the composite from a metal into a semiconductor. Credit: ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

This image shows how electrons in the gold nanorods get excited when exposed to light, then are absorbed into a thin film of zinc oxide, changing the properties of the composite from a metal into a semiconductor. Credit: ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

With funding from the Washington University International Center for Advanced Renewable Energy and Sustainability (I-CARES), Parag Banerjee, PhD, and Srikanth Singamaneni, PhD, and both assistant professors of materials science, brought together their respective areas of research.

Singamaneni’s area of expertise is in making tiny, pebble-like nanoparticles, particularly gold nanorods. Banerjee’s area of expertise is making thin films. They wanted to see how the properties of both materials would change when combined.

The research was published online in August in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

The research team took the gold nanorods and put a very thin blanket of zinc oxide, a common ingredient in sunscreen, on top to create a composite. When they turned on light, they noticed that the composite had changed from one with metallic properties into a semiconductor, a material that partly conducts current. Semiconductors are commonly made of silicon and are used in computers and nearly all electronic devices.

“We call it metal-to-semiconductor switching,” Banerjee says. “This is a very exciting result because it can lead to opportunities in different kinds of sensors and devices.”

Banjeree says when the metallic gold nanorods are exposed to light, the electrons inside the gold get excited and enter the zinc oxide film, which is a semiconductor. When the zinc oxide gets these new electrons, it starts to conduct electricity.

“We found out that the thinner the film, the better the response,” he says. “The thicker the film, the response goes away. How thin? About 10 nanometers, or a 10 billionth of a meter.”

Other researchers working with solar cells or photovoltaic devices have noticed an improvement in performance when these two materials are combined, however, until now, none have broken it down to discover how it happens, Banerjee says.

“If we start understanding the mechanism for charge conduction, we can start thinking about applications,” he says. “We think there are opportunities to make very sensitive sensors, such as an electronic eye. We are now looking to see if there is a different response when we shine a red, blue or green light on this material.”

Banerjee also says this same technology can be used in solar cells.