Dec 27 2013

Researchers have developed a way to microscopically view battery electrodes while they are bathed in wet electrolytes, mimicking realistic conditions inside actual batteries. While life sciences researchers regularly use transmission electron microscopy to study wet environments, this time scientists have applied it successfully to rechargeable battery research.

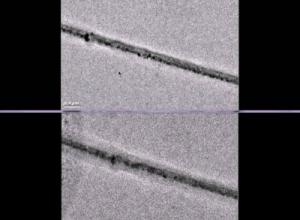

Researchers can now view a battery at work in the high magnification world of transmission electron microscopy. Liquid battery electrolytes makes this view of an uncharged electrode (top) and a charged electrode (bottom) a bit fuzzy.Credit: Gu et al, Nano Letters 2013

Researchers can now view a battery at work in the high magnification world of transmission electron microscopy. Liquid battery electrolytes makes this view of an uncharged electrode (top) and a charged electrode (bottom) a bit fuzzy.Credit: Gu et al, Nano Letters 2013

The results, reported in December 11's issue of Nano Letters, are good news for scientists studying battery materials under dry conditions. The work showed that many aspects can be studied under dry conditions, which are much easier to use. However, wet conditions are needed to study the hard-to-find solid electrolyte interphase layer, a coating that accumulates on the electrode's surface and dramatically influences battery performance.

"The liquid cell gave us global information about how the electrodes behave in a battery environment," said materials scientist Chongmin Wang of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. "And it will help us find the solid electrolyte layer. It has been hard to directly visualize in sufficient detail."

Ebb, Flow, Swell

Even though electricity seems invisible, storing and using it in batteries has some very physical effects. Charging a battery jams electrons into the negative electrode, where positively charged lithium ions (or another metal ion such as sodium) rush in to meet and hold onto the electrons. Those ions have to fit within pores within the electrode.

Powering a device with a battery causes the electrons to stream out of the electrode. The positive ions, left behind, surge through the body of the battery and return to the positive electrode, where they await another charging.

Wang and colleagues have used high-powered microscopes to watch how the ebbing and flowing of positively charged ions deform electrodes. Squeezing into the electrode's pores makes the electrodes swell, and repeated use can wear them down. For example, recent work funded through the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research--a DOE Energy Innovation Hub established to speed battery development--showed that sodium ions leave bubbles behind, potentially interfering with battery function.

But up to this point, the transmission electron microscopes have only been able to accommodate dry battery cells, which researchers refer to as open cells. In a real battery, electrodes are bathed in liquid electrolytes that provide an environment ions can easily move through.

So, working with JCESR colleagues, Wang led development of a wet battery cell in a transmission electron microscope at EMSL, the DOE's Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory on the PNNL campus. The team built a battery so small that several could fit on a dime. The battery had one silicon electrode and one lithium metal electrode, both contained in a bath of electrolyte.

Mystery Layer

When the team charged the battery, they saw the silicon electrode swell, as expected. However, under dry conditions, the electrode is attached at one end to the lithium source -- and swelling starts at just one end as the ions push their way in, creating a leading edge. In this study's liquid cell, lithium could enter the silicon anywhere along the electrode's length. The team watched as the electrode swelled all along its length at the same time.

"The electrode got fatter and fatter uniformly. This is how it would happen inside a battery," said Wang.

The total amount the electrode swelled was about the same, though, whether the researchers set up a dry or wet battery cell. That suggests researchers can use either condition to study certain aspects of battery materials.

"We have been studying battery materials with the dry, open cell for the last five years," said Wang. "We are glad to discover that the open cell provides accurate information with respect to how electrodes behave chemically. It is much easier to do, so we will continue to use them."

As far as the elusive solid electrolyte interphase layer goes, Wang said they couldn't see it in this initial experiment. In future experiments, they will try to reduce the thickness of the wet layer by at least half to increase the resolution, which might provide enough detail to observe the solid electrolyte interphase layer.

"The layer is perceived to have peculiar properties and to influence the charging and discharging performance of the battery," said Wang. "However, researchers don't have a concise understanding or knowledge of how it forms, its structure, or its chemistry. Also, how it changes with repeated charging and discharging remains unclear. It's very mysterious stuff. We expect the liquid cell will help us to uncover this mystery layer."