Feb 25 2014

Ovarian cancer accounts for more deaths of American women than any other cancer of the female reproductive system. According to the American Cancer Society, one in 72 American women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and one in 100 will ultimately die of the condition.

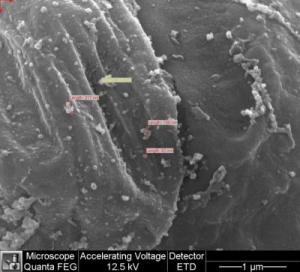

Gagomers (labeled in color) accumulating on ovarian cancer cells are shown. Credit: American Friends of Tel Aviv University (AFTAU)

Gagomers (labeled in color) accumulating on ovarian cancer cells are shown. Credit: American Friends of Tel Aviv University (AFTAU)

Now Prof. Dan Peer of Tel Aviv University's Department of Cell Research and Immunology has proposed a new strategy to tackle an aggressive subtype of ovarian cancer using a new nanoscale drug-delivery system designed to target specific cancer cells. He and his team – Keren Cohen and Rafi Emmanuel from Peer's Laboratory of Nanomedicine and Einat Kisin-Finfer and Doron Shabbat, from TAU's Department of Chemistry – have devised a cluster of nanoparticles called gagomers, made of fats and coated with a kind of polysugar. When filled with chemotherapy drugs, these clusters accumulate in tumors, producing dramatically therapeutic benefits.

The objective of Peer's research is two-fold: to provide a specific target for anti-cancer drugs to increase their therapeutic benefits, and to reduce the toxic side effects of anti-cancer therapies. The study was published in February in the journal ACS Nano.

Why chemotherapy fails

According to Prof. Peer, traditional courses of chemotherapy are not an effective line of attack. Chemotherapy's failing lies in the inability of the medicine to be absorbed and maintained within the tumor cell long enough to destroy it. In most cases, the chemotherapy drug is almost immediately ejected by the cancer cell, severely damaging the healthy organs that surround it, leaving the tumor cell intact.

But with their new therapy, Peer and his colleagues saw a 25-fold increase in tumor-accumulated medication and a dramatic dip in toxic accumulation in healthy organs. Tested on laboratory mice, the gagomer mechanism effects a change in drug-resistant tumor cells. Receptors on tumor cells recognize the sugar that encases the gagomer, allowing the binding gagomer to slowly release tiny particles of chemotherapy into the cancerous cell. As more and more drugs accumulate within the tumor cell, the cancer cells begin to die off within 24-48 hours.

"Tumors become resistant very quickly. Following the first, second, and third courses of chemotherapy, the tumors start pumping drugs out of the cells as a survival mechanism," said Prof. Peer. "Most patients with tumor cells beyond the ovaries relapse and ultimately die due to the development of drug resistance. We wanted to create a safe drug-delivery system, which wouldn't harm the body's immune system or organs."

A personal perspective

Prof. Peer chose to tackle ovarian cancer in his research because his mother-in-law passed away at the age of 54 from the disease. "She received all the courses of chemotherapy and survived only a year and a half," he said. "She died from the drug-resistant aggressive tumors.

"At the end of the day, you want to do something natural, simple, and smart. We are committed to try to combine both laboratory and therapeutic arms to create a less toxic, focused drug that combats aggressive drug-resistant cancerous cells," said Prof. Peer. "We hope the concept will be harnessed in the next few years in clinical trials on aggressive tumors," said Prof. Peer.