May 27 2015

Computational physicists have developed a novel method that accurately reveals how electrical vortices affect electronic properties of materials that are used in a wide range of applications, including cell phones and military sonar.

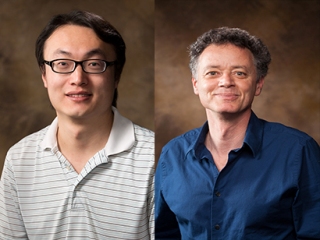

Zhigang Gui (left), Laurent Bellaiche. Photos by Matt Reynolds

Zhigang Gui (left), Laurent Bellaiche. Photos by Matt Reynolds

Zhigang Gui, a doctoral student in physics at the University of Arkansas, and Laurent Bellaiche, Distinguished Professor of physics at the U of A, along with Lin-Wang Wang at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, published their findings in Nano Letters, a journal of the American Chemical Society.

Gui used supercomputers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory to perform large-scale computations to determine the electrical properties of electrical vortices in ferroelectric materials, which generate an electric field when their shape is changed.

An electrical vortex occurs when the electric dipoles arrange themselves in an unusual swirling movement, Bellaiche said. In this ferroelectric system, electrical vortices are created and determined by the temperature of the material, Bellaiche said.

The simulations also revealed that the existence of an electrical vortex increases the band gap – the major factor determining a material’s conductivity – in this material, which offers insight to the controversial issue about the origin of the conductivity of electrical vortices.

“By changing temperature we are changing the band alignment,” Gui said. “Imagine having the same system having two different band alignments, which can lead to different applications. When decreasing temperature, our systems can transform from a Type-I band alignment, which favors light-emitting devices, to a Type-II band alignment, which favors sensors in semiconductor industries.”

The U.S. Army Research Office and the U.S. Department of Energy funded the research.