Aug 23 2018

As fungi and bacteria develop resistance to antimicrobial drugs, some scientists have hunted for alternative methods to destroy the pathogens. For instance, when bombarded with specific wavelengths of light, photosensitizing molecules, or photosensitizers, convert adjacent oxygen molecules into reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can destroy microorganisms. At present, there is no identified mechanism for pathogenic fungi and bacteria to develop resistance toward ROS.

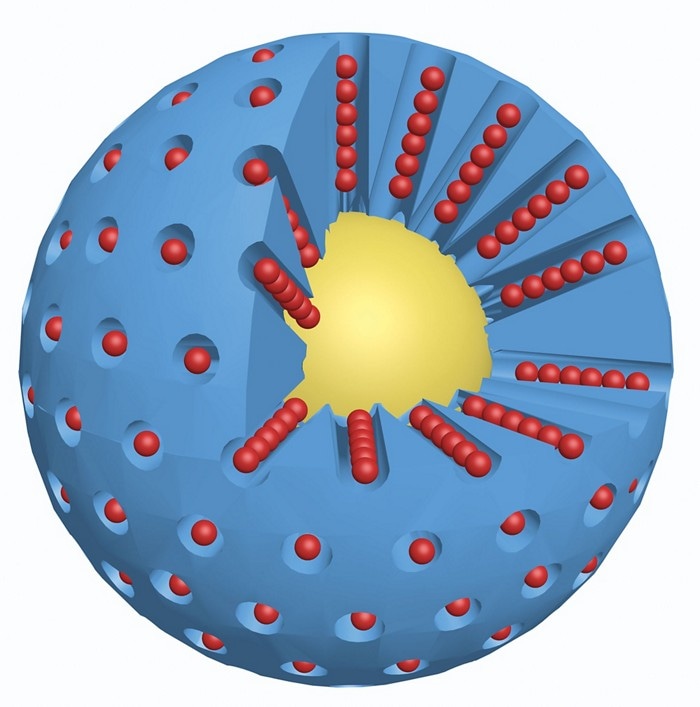

Nanoparticles with a silver core (yellow) and a silica matrix (blue) enhanced the ability of photosensitizers (red) to generate reactive oxygen species. (Image credit: Peng Zhang)

Nanoparticles with a silver core (yellow) and a silica matrix (blue) enhanced the ability of photosensitizers (red) to generate reactive oxygen species. (Image credit: Peng Zhang)

However, a number of photosensitizers are not water soluble, susceptible to aggregate in water, which decreases ROS generation. Even soluble ones pose practical problems: When they are diluted it can take a long time and plenty of light to produce sufficient ROS to kill microbes.

At the American Chemical Society national meeting in Boston, scientists reported nanoparticle formulations that intensify the ROS generation of both insoluble and soluble photosensitizers. These formulations were 10,000 to 1 million times more effective than using naked photosensitizers. Niranga Wijesiri in the lab of Peng Zhang at the University of Cincinnati presented some of the efforts during a poster session conducted in the Division of Biological Chemistry recently.

The nanoparticles have a metal core and an outer layer that clings onto the photosensitizers. Through a plasmonic effect, the metal cores yield photons when bombarded with light, increasing the volume of photons that can excite the photosensitizers.

In the design stated at the meeting, Zhang’s team used nanoparticles made using half-hydrophilic, half-hydrophobic polymers and a gold core to destroy multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus under white light with water-insoluble photosensitizers. In an associated work, the team engineered another nanoparticle that comprised a mesoporous silica matrix and a silver core. These particles used water-soluble photosensitizers and blue light to destroy acne bacteria and the fungi that cause athlete foot infections. The silver-based nanoparticles did not damage human tissue samples in lab tests.

Zhang said his team is optimistic their nanoparticle formulations can decrease the use of antibiotics and decelerate the spread of drug resistance. The eventual product, Zhang said, maybe a gel or a spray that operates under a handheld light.

Long Chiang, a chemist at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, who studies antimicrobial photosensitizers, told C&EN that the scientists’ work signifies a stimulating proof of concept. Before the formulations can be transferred to clinical trials, the scientists will need to alter the nanoparticles to prevent possible side-effects and attacks by the immune system, Chiang said.

Zhang’s team procured a patent on the technology and will be arranging pre-clinical tests in animals.