Sep 9 2020

Physicists from MIPT and the Russian Quantum Center, joined by colleagues from Saratov State University and Michigan Technological University, have demonstrated new methods for controlling spin waves in nanostructured bismuth iron garnet films via short laser pulses. Presented in Nano Letters, the solution has potential for applications in energy-efficient information transfer and spin-based quantum computing.

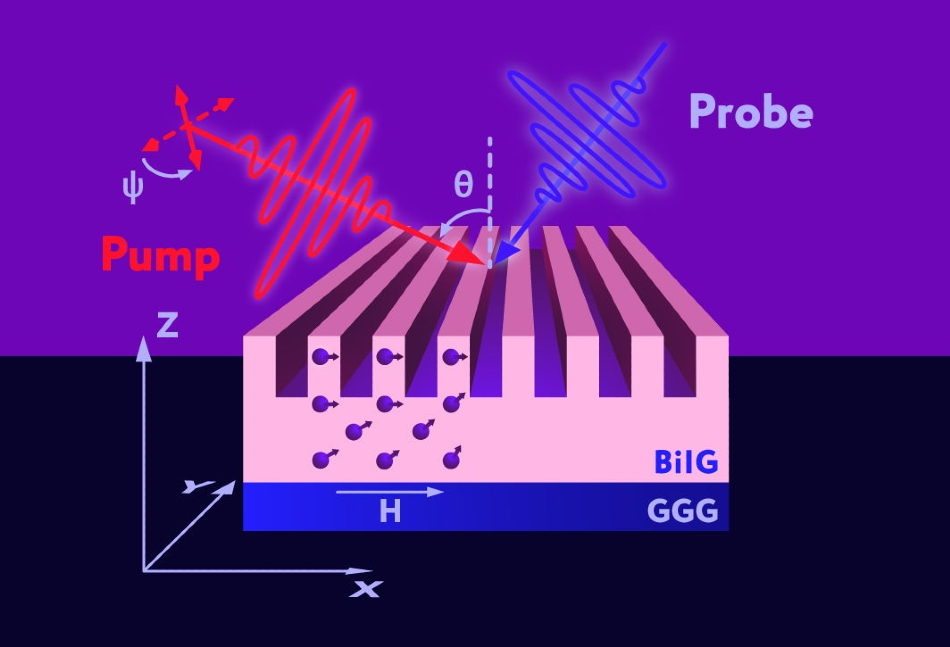

Figure 1. Schematic representation of spin wave excitation by optical pulses. The laser pump pulse generates magnons by locally disrupting the ordering of spins — shown as violet arrows — in bismuth iron garnet (BiIG). A probe pulse is then used to recover information about the excited magnons. GGG denotes gadolinium gallium garnet, which serves as the substrate. Credit: Alexander Chernov et al./Nano Letters

Figure 1. Schematic representation of spin wave excitation by optical pulses. The laser pump pulse generates magnons by locally disrupting the ordering of spins — shown as violet arrows — in bismuth iron garnet (BiIG). A probe pulse is then used to recover information about the excited magnons. GGG denotes gadolinium gallium garnet, which serves as the substrate. Credit: Alexander Chernov et al./Nano Letters

A particle’s spin is its intrinsic angular momentum, which always has a direction. In magnetized materials, the spins all point in one direction. A local disruption of this magnetic order is accompanied by the propagation of spin waves, whose quanta are known as magnons.

Unlike the electrical current, spin wave propagation does not involve a transfer of matter. As a result, using magnons rather than electrons to transmit information leads to much smaller thermal losses. Data can be encoded in the phase or amplitude of a spin wave and processed via wave interference or nonlinear effects.

Simple logical components based on magnons are already available as sample devices. However, one of the challenges of implementing this new technology is the need to control certain spin wave parameters. In many regards, exciting magnons optically is more convenient than by other means, with one of the advantages presented in the recent paper in Nano Letters.

The researchers excited spin waves in a nanostructured bismuth iron garnet. Even without nanopatterning, that material has unique optomagnetic properties. It is characterized by low magnetic attenuation, allowing magnons to propagate over large distances even at room temperature. It is also highly optically transparent in the near infrared range and has a high Verdet constant.

The film used in the study had an elaborate structure: a smooth lower layer with a one-dimensional grating formed on top, with a 450-nanometer period (fig. 1). This geometry enables the excitation of magnons with a very specific spin distribution, which is not possible for an unmodified film.

To excite magnetization precession, the team used linearly polarized pump laser pulses, whose characteristics affected spin dynamics and the type of spin waves generated. Importantly, wave excitation resulted from optomagnetic rather than thermal effects.

The researchers relied on 250-femtosecond probe pulses to track the state of the sample and extract spin wave characteristics. A probe pulse can be directed to any point on the sample with a desired delay relative to the pump pulse. This yields information about the magnetization dynamics in a given point, which can be processed to determine the spin wave’s spectral frequency, type, and other parameters.

Unlike the previously available methods, the new approach enables controlling the generated wave by varying several parameters of the laser pulse that excites it. In addition to that, the geometry of the nanostructured film allows the excitation center to be localized in a spot about 10 nanometers in size. The nanopattern also makes it possible to generate multiple distinct types of spin waves. The angle of incidence, the wavelength and polarization of the laser pulses enable the resonant excitation of the waveguide modes of the sample, which are determined by the nanostructure characteristics, so the type of spin waves excited can be controlled. It is possible for each of the characteristics associated with optical excitation to be varied independently to produce the desired effect.

“Nanophotonics opens up new possibilities in the area of ultrafast magnetism,” said the study’s co-author, Alexander Chernov, who heads the Magnetic Heterostructures and Spintronics Lab at MIPT. “The creation of practical applications will depend on being able to go beyond the submicrometer scale, increasing operation speed and the capacity for multitasking. We have shown a way to overcome these limitations by nanostructuring a magnetic material. We have successfully localized light in a spot few tens of nanometers across and effectively excited standing spin waves of various orders. This type of spin waves enables the devices operating at high frequencies, up to the terahertz range.”

The paper experimentally demonstrates an improved launch efficiency and ability to control spin dynamics under optical excitation by short laser pulses in a specially designed nanopatterned film of bismuth iron garnet. It opens up new prospects for magnetic data processing and quantum computing based on coherent spin oscillations.

The study was supported by the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education.