What is a peptide, and how is it different than a protein? Just like a protein, a peptide also has a chain of natural amino acids, but it is much shorter, say 10-30 units, compared to those in proteins, which could be hundreds and thousands of units long. Along with DNA (genetic code), polysaccharides (sugars) and lipids (fats), proteins are the fourth major building blocks that make life viable.

Proteins collect ions and transport them, carry out enzymatic functions, and constitute the major structures of the cells. Proteins, therefore, are the key building blocks of organisms carrying out life’s functions making it dynamic. For decades, scientists have been trying to understand how the sequence of amino acids in proteins are correlated to their molecular architecture so that one can predict their specific functions. The understanding of the protein’s shape and function is crucial to discover the origin of diseases and designing of vaccines and drugs. Proteins can also be useful for technological applications such as in tissue engineering and designing biosensors for diagnostics. So far, however, predicting protein’s structure has been elusive, even by using the recently developed computational models such as Alpha-Fold, based on Google’s deep learning algorithms. Using proteins, therefore, has still not been practical because of their enormous size and unpredictable functions.

Image Credit: © 2023 American Chemical Society

What is a peptide, and how is it different than a protein? Just like a protein, a peptide also has a chain of natural amino acids, but it is much shorter, say 10-30 units, compared to those in proteins, which could be hundreds and thousands of units long. Along with DNA (genetic code), polysaccharides (sugars) and lipids (fats), proteins are the fourth major building blocks that make life viable. Proteins collect ions and transport them, carry out enzymatic functions, and constitute the major structures of the cells. Proteins, therefore, are the key building blocks of organisms carrying out life’s functions making it dynamic. For decades, scientists have been trying to understand how the sequence of amino acids in proteins are correlated to their molecular architecture so that one can predict their specific functions. The understanding of the protein’s shape and function is crucial to discover the origin of diseases and designing of vaccines and drugs. Proteins can also be useful for technological applications such as in tissue engineering and designing biosensors for diagnostics. So far, however, predicting protein’s structure has been elusive, even by using the recently developed computational models such as Alpha-Fold, based on Google’s deep learning algorithms. Using proteins, therefore, has still not been practical because of their enormous size and unpredictable functions.

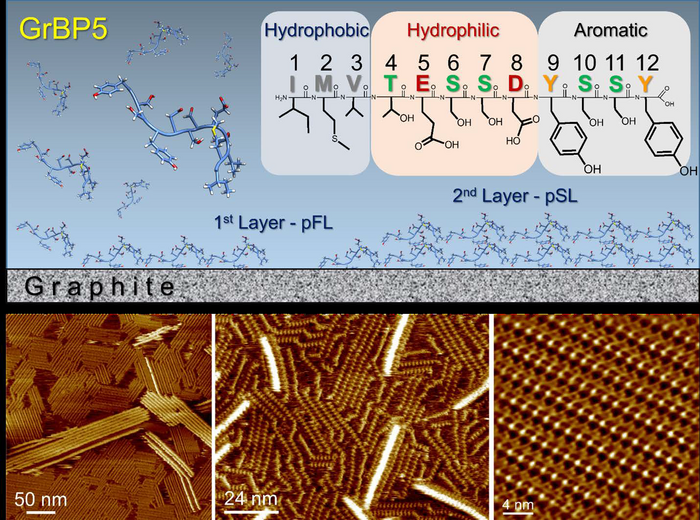

Peptides, on the other hand, are smaller versions of proteins with similar roles, and therefore are more practical as their roles also rely on the amino acid sequences that lead to their folding patterns. Because of their smaller sizes and disordered molecular structures, for years, peptides have been considered to be not so useful because of having unpredictable functions. The “floppy” structures of peptides, however, could be turned into an advantage if these small biomolecules could be engineered using an interdisciplinary approach, combining biology, engineering and predictive modeling. This is exactly what a team of scientists, led by Ayhan Yurtsever, Linhao Sun, Kaito Hirata, and Takeshi Fukuma at Kanazawa University and their colleagues, Mehmet Sarikaya, a materials scientist, and his team, at the University of Washington, have accomplished. Combining the Seattle-Team’s expertise in genetic engineering in designing peptides that have exclusive affinity to technological solids and Kanazawa-Team’s expertise in molecular imaging under biologically benign conditions, the scientists have demonstrated self-organization of the peptides on a solid surface and visualized them at unprecedented molecular resolution, the knowledge is essential in designing hybrid biomolecular nanodevices for use in biology and technology alike.

The scientists accomplished this feat by combining their expertise in their respective fields. The peptides used were selected by an ingenious approach, called directed evolution, normally used for selecting cancer drugs for a specific tumor by molecular biologists. In this case, the molecule used, called graphite binding peptide, was genetically selected using graphite as the substrate, by a materials scientist. Armed with the expertise gained in examining molecular architectures in aqueous solutions, the Kanazawa team demonstrated the way the peptide self-organizes on atomically flat graphite surface is in patterns, predicted by computational modeling of the peptides. Knowing that the way the proteins carry out their function is through molecular recognition of their biological substrates (for example, DNA, proteins, enzymes, other biomolecules, or diseased cells), the scientists realized that the peptides predictably self-organize on graphite, a synthetic substrate, because of the same molecular recognition principle as in biology.

The origin of molecular recognition and its control via designing a new amino acid sequence is the holy grail in biology as, if the process can be controlled, then many kinds of drugs and vaccines can be designed based on the target (diseased) molecule or the substrate. Here, the target is a technological material, graphite, or it can also be graphene, its single atomic layer version, a highly significant technological material of the last two decades. In this work, the Kanazawa-Seattle collaborative teams have discovered that the graphite binding peptide not only recognizes graphite atomic lattice but also forms its own molecular crystal thereby establishing a coherent, continuous, soft interface between the peptide and the solid. “The capability of seamlessly bridging biology with functional solids at the molecular level is the critical first step towards creating biology-inspired technologies and is likely to lend itself in the design of biosensors, bioelectronics, and peptide-based biomolecular arrays, and even logic devices, all hybrid technologies of the future,” the scientists say. The teams are currently busy in expanding their discovery in addressing further questions, such as the effects of mutations, structured water around peptides, on other solid substrates, and physical experiments across the peptide-graphite interfaces towards establishing the firm scientific foundations for the development of the next generation biology-inspired technologies.

Background

Peptide is a small protein, the key biomolecule that enable life. Peptides composed of amino acids (only 20 found in nature), usually less than 20 strong together forming a chain. The sequence of the amino acids is important as this dictate the molecular shape of the peptide and its function, for example binding to a molecule, ion or a surface, or they can be tiny enzymes, synthesizing molecules or solids. Using peptides is challenging because, being small, they are intrinsically disordered, that mean they have unpredictable folding patterns, unlike protein, which are large and form stable molecular conformations. The peptide used in this work was genetically selected, using a phage display library, a directed evolution approach. Since the substrate solid used for selection was graphite, the peptides are called graphite-binding peptides. As the name suggests, their function is predictable, because they exclusively bind to graphite. As this work demonstrated, they also form crystal lattices on cleaved graphite surface, a key finding of scientific and technological importance.

Funding Information

This work was primarily supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 20H00345, 21H05251, and No. 20K05321) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (MEXT). The research (MS, SR, HZ) is supported by NSF through the DMREF program (via Materials Genome Initiative) under grant numbers DMREF DMR# 1629071, 1848911, and 1922020. This work was also partially supported by a Kanazawa University NanoLSI Transdisciplinary Research Promotion Grant, World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan.