Nov 7 2012

The use of DNA strands as nano building materials is on the way to creating revolutionary new opportunities in the development of medicine, optics and electronics.

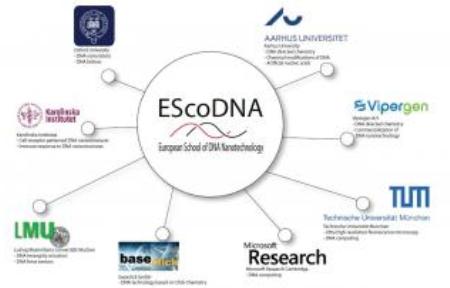

EScoDNA Partners

EScoDNA Partners

The idea of using artificial DNA strands as tiny self-assembly kits was originally developed by American scientists in the 1990s, and the continued development has in great parts taken place in the USA.

However, during the last decade European researchers have contributed significantly to the progress of this rapidly evolving field, and have built up strong expertise at the European universities to be able to set up a joint graduate school in this subject, enhancing European research and development in DNA nanotechnology. The school will mainly cover fundamental research, but it is also set up to promote innovations and the development of commercial applications.

EScoDNA

The new graduate school is called the European School of DNA Nanotechnology (EScoDNA), and it has been awarded approximately EUR 4 million as an Initial Training Network (ITN) under the European Commission's Marie Curie Actions research fellowship programme. EScoDNA will foster the development of a new generation of scientists with the skills required to meet futures challenges in bionanotechnology, from fundamental science to novel applications.

"We have an excellent pool of talent at the undergraduate level: if we provide excellent conditions to study DNA nanotechnology we will be able to educate a pool of highly competent European-based PhDs and we will gain access to some of the best young researchers in the world," says Professor Gothelf at Aarhus University, Denmark, who is the coordinator of the EScoDNA programme.

By addressing the present shortage of experienced researchers in this field, EScoDNA will also promote the foundation of new bionanotechnology start-up companies and the strong links between industrial partners and research labs within this training network will help to establish the rising field of DNA nanotechnology as a market for biotechnology-related industries.

Initially fourteen new PhD students and two postdoctoral fellows will join the network in 2013. The new DNA nano researchers will be distributed among the participating universities as follows:

- Aarhus University (Denmark) (3)

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Germany) (2)

- Technical University of Munich (Germany) (2)

- Karolinska Institute (Sweden) (2)

- University of Oxford (UK) (3)

Also taking part in the programme are the private companies Vipergen ApS (Denmark) and baseclick GmbH (Germany), each of which will be allocated one PhD student and one postdoctoral fellow. Microsoft Research Cambridge (UK) is contributing to the programme with teaching and supervision.

Interdisciplinary

Because DNA nanotechnology is to a large extent an interdisciplinary discipline, the new school expects to find candidates among chemists, molecular biologists, physicists and possibly computer scientists. Each participating body in the network will recruit students from abroad, and each student will spend a period of more than six months at the other institutions in the network. The school will also gather the students twice a year to attend workshops to educate them and to coordinate the joint research projects.

By providing quality teaching, EScoDNA would like to boost career options for the young researchers in both the public and the private sectors, as well as strengthening European competitiveness in this field. The business partners will thus also contribute with teaching in the commercial exploitation of new technology, management and entrepreneurship.

"We expect the efforts of the young researchers in EScoDNA to generate a number of ground-breaking results that will be significant for both the academic world and the business sector," says Professor Gothelf.

Facts

DNA nanotechnology is based on the ability of DNA sequences to bind to their complementary counterparts. In other words, DNA strands can find their designated partner sites, anneal to each other and this way build up specific man-made patterns. They can be programmed to assemble themselves in precisely defined three-dimensional shapes that can have widely varying components attached, such as proteins, organic molecules, carbon nanotubes or other nanoparticles.